Collaborative Practice for Neurodivergent Children: The role of Parents in Allied Health Therapy

Children’s brains develop best in the context of trusting relationships with parents and caregivers. Since relationships build brains, we must value parents as the most profound influence in their child’s life (Delahooke, 2020). Given that parents are the most important people in a child’s life they should also always be playing a central role in their child’s therapy (Golding & Hughes, 2020).

The development of a child within a family influences the entire family system, including how relationships and emotion regulation abilities progress. This symbiotic relationship is demonstrated when considering the needs of a neurodivergent child. Those needs impact how their family functions, while at the same time the functioning of the family system will impact what challenges the child encounters. Therefore, a whole of family approach is useful for easing stress throughout the entire family system (Long, 2023).

The revised International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) shifts understanding of disability from a biomedical model to a biopsychosocial model. This means bodily functions, bodily structure, activity, participation, the environment, and personal factors are all considered as contributing to disability. This model encourages consideration of the child’s participation in real world contexts, their functional use of skills and their family network when developing goals for therapy (Phoenix, et al., 2019).

To understand the impact of the family system when supporting a neurodivergent child, it is important to be aware of challenges faced by their parents and families. It has been found that families of Autistic children have higher rates of depression, anxiety and stress than other families (McKenzie, et al., 2019). Challenging behaviours, communication difficulties, and increased co-regulation needs are all thought to contribute to the mental health challenges these parents experience (Lievore, et al., 2024). Given the genetic component of Autism, many parents of Autistic children may be newly identified or unidentified autistic adults. Long-term misunderstanding of their own Autistic needs is likely to also be a contributing factor to parent’s mental health challenges (Long, 2023).

Research has shown that families waiting for a diagnosis are at high risk of developing mental health problems due to the increased stress of managing their autistic child’s needs without appropriate support (McKenzie, n.d.). Families with an Autistic child report experiencing more parental stress than other families. Parental stress is defined as negative feelings prompted by the demands of parenting when they exceed an individual’s resources (McKenzie, et al., 2022). Parental stress can then influence a child’s emotional regulation due to maladaptive parenting techniques such as controlling methods or harsh discipline. This parental behaviour will then often exacerbate the child’s anxiety which is often externalised as challenging or distressing behaviour (Lievore, et al., 2024).

Parental stress can be further exacerbated when unable to secure appropriate resources or when extended family members challenge parenting decisions. Differing views on how to parent and support an Autistic child can also strain the relationship between parents. These factors can all lead to burnout within the family system due to unrelenting demands and stressors (Malhi & Gogineni, 2023). Increased strain within the family environment can then contribute to increased emotional dysregulation, and mental health difficulties for Autistic children.

The co-occurring mental health conditions Autistic children experience might not be identified as an issue separate to their autism and would then not be referred for appropriate specific mental health support. Parents report that a lack of psychological well-being in their Autistic child exacerbates emotional dysregulation which leads to an increase in challenging behaviour (McKenzie, et al., 2019). This demonstrates how a lack of mental health support can result in escalating challenges, putting an additional strain on their family system (Burton & Fox, 2023).

Stressful and traumatic life events have been found to be an underlying risk factor for the co-occurring mental health conditions that are common in Autistic individuals. One incidence can be the trauma of invalidation that occurs when there is a perception of being invalidated by the social environment. For Autistic individuals this can occur through social rejection, and when a highly distressing experience like a schedule change or an unpleasant texture is diminished or dismissed (Fuld, 2018).

Decreasing significant stressors and promoting an environment that is nurturing, supportive and affirmative of the Autistic experience should inform treatment goals and strategies. For these interventions to be effective for an Autistic individual everybody within their system, especially their family, need to be supportive of these changes. Collaborative practice that promotes within the whole family a neurodiversity perspective, helps create an affirmative environment, and facilitates healthy coping strategies will offer protective factors for Autistic individuals’ long term mental health (Fuld, 2018).

Autistic individuals often experience high levels of social and economic injustice throughout their life, such as Autistic children feeling socially isolated or performing poorly in school (Bishop-Fitzpatrick, et al., 2019). Autistic young adults have decreased well-being and fewer positive emotions than their peers (Lord, et al., 2020) and less than half of Autistic young adults are able to maintain a job (Solomon, 2020). While Autistic adults are frequently excluded from participation in their communities, including suitable employment (Bishop-Fitzpatrick, et al., 2019).

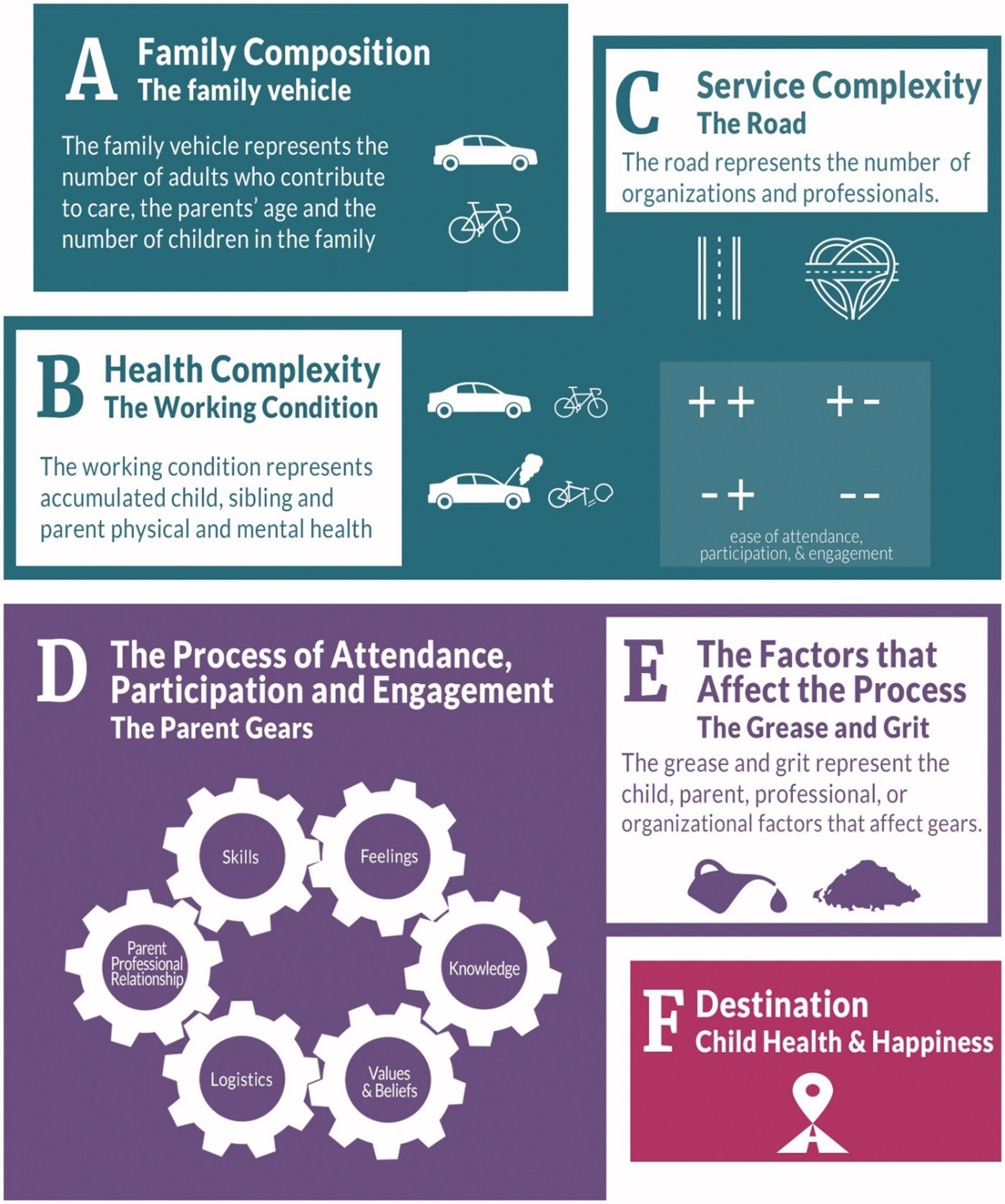

Autistic individuals and their families can experience increased financial burden due to costs associated with supporting their Autistic needs and the commonly co-occurring physical health issues they experience. There is also an increased likelihood of disruptions to childcare and education, often due to suspension or school-based trauma. This then impacts parental employment and their income (Bishop-Fitzpatrick, et al., 2019) placing further stress on the already strained family system. Figure 1 demonstrates the variety of factors that all contribute to a family’s ability to engage with therapy to support their child.

Figure 1. The Phoenix Theory of Attendance, Participation and Engagement (Phoenix, et al., 2019)

Autistic young adults have some of the lowest rates of autonomy and self-determination among their peers. Self-determination skills help young adults make choices, set goals, and assist in problem-solving, self-monitoring, and self-advocating (Cheak-Zamora, et al., 2020). Autistic traits may make it difficult to develop skills to achieve self-determination, while another factor is likely that current school, work, and community systems are not designed to support acceptance of differences (Andrews, et al., 2023). Autistic youth with high perceptions of life satisfaction also have higher levels of self determination (White, et al., 2018). Working with Autistic youth and their families to build self-determination skills will support them to be independent and exert autonomy in their daily lives (Lord, et al., 2020), therefore also increasing the Autistic individuals’ quality of life.

Parents reported that their child’s happiness is a driving force behind their engagement with therapy (Phoenix, et al., 2019). Despite its challenges, some parents recognise that through parenting their Autistic child they have become more appreciative, patient, and compassionate. When families have the appropriate skills and knowledge to support their child, they can cope with difficulties and achieve good family relationships (McKenzie, et al., 2019). It is important for clinicians to capitalise on the determination and willingness of parents to provide a positive future for their children and family when providing therapy (McKenzie, n.d.).

Trust between a child and their parent can be inadvertently damaged when traditional parenting methods are used. Even when a threat is invisible to parents their child’s brain and body will register threats that set off their threat-detection system. This results in the child’s autonomic nervous system dictating their behaviour, removing the child’s ability to consciously control their behaviour. Any punishment or negative consequences at this point will then send the child’s nervous system into increasing levels of distress (Delahooke, 2020).

Involving parents in their child’s therapy allows parents to learn different ways of parenting their child. Children then experience their parents differently which can help them recover trust and begin to feel secure within their families (Golding & Hughes, 2020). The benefits experience by parents when involved in their child’s therapy will likely reinforce to them that their parenting can make a significant difference in their child’s life (Golding & Hughes, 2020) thus providing important motivation. Given that families are the centre of learning for children, a family-centred approach is essential to support child development (Klatte, et al., 2020).

Studies have found positive benefits with including parents in their children’s physical and mental health treatments (Lebowitz , et al., 2020) (Kurzweil, 2023) (Phoenix, et al., 2019). Evidence-based treatments for conditions such as ADHD, depression, and anxiety all feature parent-focused intervention strategies (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015) often using a Systemic family therapy approach (McKenzie, et al., 2019). A cohesive collaborative approach such as psychoeducation can assist families to understand Autism, learn strategies that support challenging behaviour and mental health difficulties, improve communication between family members, and enhance family functioning (McKenzie, et al., 2019).

Psychoeducation is an opportunity for clinicians to explain how a traditional approach to Autism is restrictive and oppressive for autistic people and their families. It can result in “oughtism” or ableism where parents are unable to challenge the view that behaviours and traits of autistic people need to be hidden so they fit into society and act and look more like neurotypical (Simon, et al., 2020). Explaining the neurodiversity paradigm allows for new understandings of autism and provides space to talk differently and positively about aspects of autism. This can then improve the relationship between families and clinicians (Long, 2023).

The term Collaborative Practice used throughout this article is a general term to refer to any parent focused, family centred intervention. There are many approaches that have been developed to implement Collaborative Practice that can be categorised by two different methods. The first method involves parents in direct therapy sessions with their child. The second occurs without the child present to allow the clinician & parent to talk openly.

Important elements of Collaborative Practice include mutually agreed upon goals, shared implementation, and integrating child and family needs preferences and routines (Klatte, et al., 2024). Parents form an important part of therapy by ensuring follow-through with home action plans, changing their parenting behaviour, and supporting the child’s efforts to learn new skills. Observational and qualitative research studies have demonstrated that when Collaborative Practice is lacking in clinical settings any therapeutic changes achieved during therapy are less likely to be transferred to the home environment (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015).

Collaborative practice has been found to benefit Autistic children more than those with comparable conditions, possibly because parents are often present with their child allowing for more opportunity to utilise strategies and interventions. Improvements in social, language, communication, and life skills, along with a decrease in challenging behaviours were all noted. These benefits are consistent when implemented by either or both parents and are significant compared with usual treatments and waitlist conditions (Cheng, et al., 2023).

Given the key role parents play in the successful intervention of their children; it is necessary for clinicians to understand how to communicate with, relate to, and coach parents effectively to achieve sustainable long-term therapy goals (Lage & Snider, 2022). Collaborative Practice helps clinicians establish a respectful, equitable, and complementary partnership with parents. It places equal emphasis on the important roles of both parents and clinicians within the therapeutic process (Klatte, et al., 2020).

The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDC, n.d.) considers it best practice for clinicians to empower parents to understand and implement strategies that support their child. One method of Collaborative Practice that empowers parents is Parent-Mediated Therapy (PMT), it does this by including parents in sessions so the clinician can guide positive interactions between parent and child. Research has shown that improvements gained through PMT are sustained after the conclusion of therapy (Klowan, et al., 2023).

The Parent Coaching Approach (PCA) aims to guide parents to identify and implement solutions that are effective for their family system (Occupational Therapy Helping Children, 2024). PCA builds parents’ confidence regarding what works for their children, so it becomes easier for them to problem solve issues as they arise at home. PCA has been found to have positive outcomes for both parents and children, with children who have challenges in sensory processing and sensory integration (Miller-Kuhaneck & Watling, 2018).

Let’s Cope Together (Korpilahti-Leino, et al., 2022) and Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions (Lebowitz , et al., 2020) are Collaborative Practice programs that provide parents with skills to support their child experiencing anxiety. Parents reported an increase in skills that eased both their anxiety and their children’s anxiety and evaluation has shown that the programs may be just as effective as CBT for treating anxiety in children.

The therapeutic model PACE, named from the four core elements of Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy, builds on Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy (DDP) (Golding & Hughes, 2020). Studies of parenting programmes based on DDP have shown that parents feel more effective and competent parenting their children, have increased insight into their child’s mind and notice a positive difference to their child and the family unit (Golding & Hughes, 2020). Parents reported that DDP suited their unique situation because it promoted acceptance, helped build trust, and supported co-regulation (Gurney-Smith & Wingfield, 2018).

Recently there has been several parent-mediated Collaborative Practice programs developed to support Autistic individuals and their families. These include Paediatric Autism Communication Therapy (Leadbitter, et al., 2020), Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (Allen, et al., 2023), Multifamily Therapy (Lo, et al., 2023), and Systemic Autism-related Family Enabling (McKenzie, n.d.). These programs were found to have benefits such as improvements in children’s communication and behaviour, an increase in parental confidence and self-efficacy, enhanced family relationships, and an improvement in the families ability to cope with challenges.

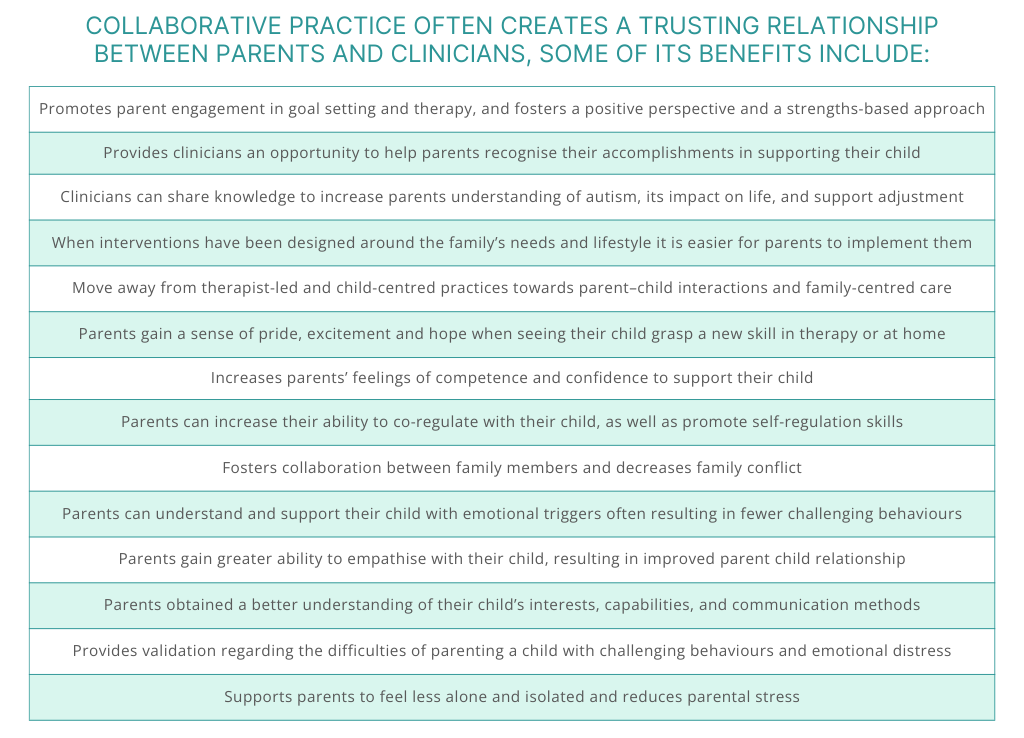

Sources: (Golding & Hughes, 2020) (Allen, et al., 2023) (Klowan, et al., 2023) (Meehan, 2023) (University of Plymouth, n.d.) (Leadbitter, et al., 2020) (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015) (Lo, et al., 2023) (McKenzie, et al., 2022) (Malhi & Gogineni, 2023) (Klatte, et al., 2020) (Phoenix, et al., 2019).

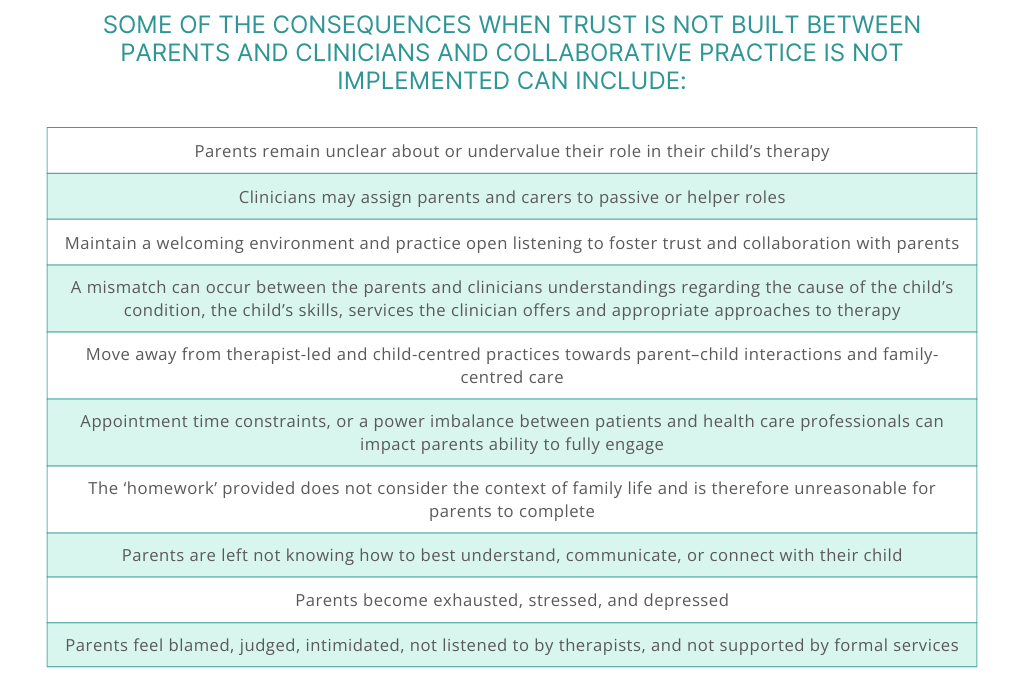

The competing demands on parents time, priorities and energy means that all therapeutic interventions need to be practical, feasible and accessible. Many parents reported challenges relating to the time commitment of therapy and home practice, the length of sessions, and the inconvenience, unfamiliarity and autism-unfriendliness of therapy venues. If not addressed by clinicians such challenges may contribute to increased parental stress, or considerations of non-participation (Leadbitter, et al., 2020).

Sources: (Klatte, et al., 2020) (Phoenix, et al., 2019) (Klowan, et al., 2023) (Lievore, et al., 2024) (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015) (Klatte, et al., 2024).

Despite the evidence regarding the benefits of Collaborative Practice only 25% of clinicians reported their training as encouraging them to choose to work with parents. This suggests clinicians working with children require further education about the benefits of collaborative practice (Kurzweil, 2023). Reported barriers impacting clinicians’ ability to move towards collaborative practice include their motivation, a lack of opportunities, rigid models of service delivery, time, and financial constraints (Klatte, et al., 2024).

Sources: (Klowan, et al., 2023) (Klatte, et al., 2024) (Lage & Snider, 2022) (Phoenix, et al., 2019) (Leadbitter, et al., 2020) (Lievore, et al., 2024).

Sources: (Tucker, 2018) (TherapyConnect, 2013) (Malinski, 2021) (Kindred, 2023).

The Collaborative Practice approaches discussed in this article draw from a variety of disciplines including Psychology, Speech Therapy, Occupational Therapy, Social Work, and Family Therapy. The discipline of Social Work naturally aligns with the goals and techniques of Collaborative Practice. By using curiosity, and an inclusive and relational approach social workers listen to and validate the stories of neurodivergent people and support families to discovering their unique narrative (Long, 2023). Social work values share many similarities with Autistic values including integrity, honesty, equity, and a desire for social justice (Guthrie, 2023), which often makes them a suitable clinician to support Autistic individuals.

The goal of the social work profession is to promote full and meaningful inclusion in society for the most vulnerable communities, including the neurodivergent community, whose members experience high levels of social and economic injustice. Social workers also work with Autistic clients on themes associated with regaining a sense of power, a sense of connection to others, and a sense of both physical and emotional safety (Fuld, 2018). These social work approaches aim to reduce disparities and injustice for neurodivergent individuals and their families by responding to their unique needs and strengths (Bishop-Fitzpatrick, et al., 2019).

The family system has a symbiotic relationship in that a child’s developmental needs effects their parent’s capacity and parenting decisions, then the way they parent will impact their child’s nervous system and can result in increased challeging behaviour. Parents have the most profound influence on their child’s life and any external stressors experience by parents will impact their relationship with their child. Therefore, the high levels of social and economic injustice experienced by neurodivergent families can further impact their quality of life if those issues are not addressed.

Parents of neurodivergent individuals experience many different stressors including financial, complex family dynamics, multiple neurodivergent family members with competing needs, mental health challenges, and overwhelm managing their Autistic child’s emotional and behavioural needs. For therapy to be effective when a variety of these stressors are present it needs to be tailored to the needs of the entire family, not just the Autistic individual. This can best be achieved when parents and clinicians work collaboratively by sharing information, setting goals together and developing strategies that are achievable within the family system.

This collaborative practice can be achieved by parents being directly involved in the child’s therapy session or having sessions between parents and clinicians without the child present. There are many ways this can occur depending on the needs of the family and child. If a child often finds it hard to concentrate for the entire therapy session, consider using the end of the session for the clinician and parents to work together, or utilise telehealth as a way for the clinician and parents to have a session together every few months. When children are unable to engage with therapy it can be a good opportunity for collaborative practice to occur solely between parents and clinicians, to ensure that parents are well supported while helping their child in distress.

Social workers have the skills and values to work collaboratively with parents and families by providing them with psychoeducation and supporting them to make change in their lives to improve their personal and social well-being. Other clinicians may also choose to implement Collaborative Practice, yet research suggests it is not currently ingrained in all disciplines of allied health practice. Therefore, it is important for both clinicians and parents to be aware of the many benefits of Collaborative Practice and then work together to develop this imperative method.

References

Allen, K. et al., 2023. Parent–Child Interaction Therapy for Children with Disruptive Behaviors and Autism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Volume 53, p. 390–404.

Andrews, H. E., Hedley, D. & Bury, . S. M., 2023. The Relationship Between Autistic Traits and Quality of Life: Investigation of Indirect Effects Through Self-Determination. Autism in Adulthood ahead of print.

Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L. et al., 2019. Autism spectrum disorder and the science of social work: A grand challenge for social work research. Social Work Mental Health, 17(1), pp. 73-92.

Burton, L. & Fox, C., 2023. Are families supported to come to terms with an autism diagnosis? A service evaluation of referrals to family therapy for young people with autism in one NHS trust.. Journal of Family Therapy, Volume 45, p. 154–166.

Cheak-Zamora, N. C., Maurer-Batjer, A., Malow, B. A. & Coleman, A., 2020. Self-determination in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 24(3), pp. 605-616.

Cheng, W. M. et al., 2023. Effects of Parent-Implemented Interventions on Outcomes of Children with Autism: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Volume 53, p. 4147–4163.

Delahooke, M., 2020. Beyond Behaviors: Using Brain Science and Compassion to Understand and Solve Children’s Behavioral Challenges. s.l.:John Murray.

Fuld, S., 2018. Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Impact of Stressful and Traumatic Life Events and Implications for Clinical Practice. Clinical Social Work Journal, Volume 46, p. 210–219.

Golding, K. S. & Hughes, D. A., 2020. Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy (DDP): Using Relationships to heal children traumatised within their early relationships. Adoption Today.

Gurney-Smith, B. & Wingfield, M., 2018. Adoptive parents’ experiences of dyadic developmental psychotherapy. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

Guthrie, J., 2023. Swimming with the Current But against the Tide: Reflections of an Autistic Social Worker. The British Journal of Social Work, 53(3), p. 1700–1710.

Haine-Schlagel, R. & Walsh, N. E., 2015. A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(2), pp. 133-150.

Kindred, 2023. How to Make the Most of Therapy for Your Child. [Online]

Available at: https://kindred.org.au/resources/how-to-make-the-most-of-therapy-for-your-child/

[Accessed 01 03 2024].

Klatte, I. S. et al., 2024. Collaboration: How does it work according to therapists and parents of young children? A systematic review. Child: Care, Health and Development, 50(1).

Klatte, I. S. et al., 2020. Collaboration between parents and SLTs produces optimal outcomes for children attending speech and language therapy: Gathering the evidence.. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, Volume 55, pp. 618-628.

Klowan, A., Kadlec, M. B. & Johnston, S., 2023. The Parents’ Perspective: Experiences in Parent-Mediated Pediatric Occupational Therapy for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11(1).

Korpilahti-Leino, T. et al., 2022. Single-Session, Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to Improve Parenting Skills to Help Children Cope With Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Feasibility Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(4).

Kurzweil, S., 2023. Involving Parents in Child Mental Health Treatments: Survey of Clinician Practices and Variables in Decision Making. The American Journal of Psychotherapy, 76(3), pp. 107-114.

Lage, C. R. & Snider, J., 2022. Collaborative Practices in Early Childhood Intervention: the case for explicitly striving for maximal participation of families. The Allied Health Scholar, 3(2), pp. 1-8.

Leadbitter, K., Macdonald, W., Taylor, C. & Buckle, K. L., 2020. Parent perceptions of participation in a parent-mediated communication-focussed intervention with their young child with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 24(8).

Lebowitz , E. R. et al., 2020. Parent-Based Treatment as Efficacious as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Childhood Anxiety: A Randomized Noninferiority Study of Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(3), pp. 362-372.

Lievore, R., Lanfranchi, S. & Mammarella, I. C., 2024. Parenting stress in autism: do children’s characteristics still count more than stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic?. Current Psychology, Volume 43, p. 2607–2617.

Lo, . J. W. K., Ma, J. . L. C. & Wong, J. C. Y., 2023. The Feasibility and the Therapeutic Process Factors of Online vs. Face-to-Face Multifamily Therapy for Adults with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder in Hong Kong: A Multi-Method Study.. Contemporary Family Therapy.

Long, É., 2023. “Difference which makes a difference” (Bateson, 1972): how the neurodiversity paradigm and systemic approaches can support individuals and organisations to facilitate more helpful conversations about autism. Journal of Social Work Practice, 37(1), pp. 109-118.

Lord, C. et al., 2020. Work, living, and the pursuit of happiness: Vocational and psychosocial outcomes for young adults with autism.. Autism, 24(7), pp. 1691-1703.

Malhi, N. K. & Gogineni, R. R., 2023. Supporting Families With Autistic Children. [Online]

Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psychiatrys-think-tank/202308/supporting-families-with-autistic-children

[Accessed 13 02 2024].

Malinski, K., 2021. Parenthood Understood. [Online]

Available at: https://parenthoodunderstood.com/an-insiders-guide-to-getting-the-most-out-of-your-childs-therapy/

[Accessed 01 03 2024].

McKenzie, B., n.d. Systemic Autism-related Family Enabling (SAFE): an early intervention for families of autistic children. [Online]

[Accessed 13 02 2024].

McKenzie, R. et al., 2019. SAFE, a new therapeutic intervention for families of children with autism: study protocol for a feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open.

McKenzie, R. et al., 2022. Family Experience of Safe: A New Intervention for Families of Children with a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Contemporary Family Therapy, Volume 44, p. 144–155.

Meehan, A., 2023. 8 reasons why involving parents in a child’s therapy is essential. [Online]

Available at: https://www.meehanmentalhealth.com/the-playful-therapist-blog/the-power-of-parent-engagement-8-reasons-why-parent-involvement-is-essential-in-play-therapy

[Accessed 03 02 2024].

Miller-Kuhaneck, H. & Watling, R., 2018. Parental or Teacher Education and Coaching to Support Function and Participation of Children and Youth With Sensory Processing and Sensory Integration Challenges: A Systematic Review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(1).

Occupational Therapy Helping Children, 2024. Parent Coaching. [Online]

Available at: https://www.occupationaltherapy.com.au/parent-coaching/

[Accessed 03 02 2024].

Phoenix, M., Jack, S. M., Rosenbaum, P. L. & Missiuna, C., 2019. A grounded theory of parents’ attendance, participation and engagement in children’s developmental rehabilitation services: Part 2.. The journey to child health and happiness.

Simon, G. et al., 2020. Autism and Systemic Family Therapy. In: The Handbook of Systemic Family Therapy. s.l.:s.n.

Solomon, C., 2020. Autism and Employment: Implications for Employers and Adults with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Volume 50, p. 4209–4217.

TherapyConnect, A., 2013. Helping families understand therapy for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. [Online]

Available at: https://www.therapyconnect.amaze.org.au/producing-best-outcomes/reality-check/

[Accessed 03 02 2024].

Tucker, K. J., 2018. The Importance of Parent Involvement. [Online]

Available at: https://www.carolinapeds.com/blog/2018/12/the-importance-of-parent-involvement

[Accessed 03 02 2024].

University of Plymouth, n.d. Systemic Autism-related Family Enabling. [Online]

Available at: https://www.plymouth.ac.uk/research/education/university-practice-partnerships/research-in-practice/systemic-autism-related-family-enabling

[Accessed 13 02 2024].

White, K., Flanagan, T. D. & Nadig , A., 2018. Examining the Relationship Between Self-Determination and Quality of Life in Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, Volume 30, p. 735–754.